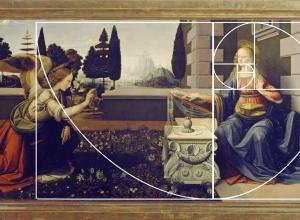

Art and science met again when, as far back as ancient Egypt, painters discovered the fixative qualities of egg whites, applying them to colored pigments. In the year 500, the first dome topped the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, built not by architects, but mathematicians. A thousand years later, Renaissance artists adopted mathematical formulas to create the impression of depth.

In modern history, the marriage of art and science is evident in the works of the impressionists and pointillists who relied on the human eye, not the palette, to mix colors, just as painters of the colorist movement did in the 1960s.

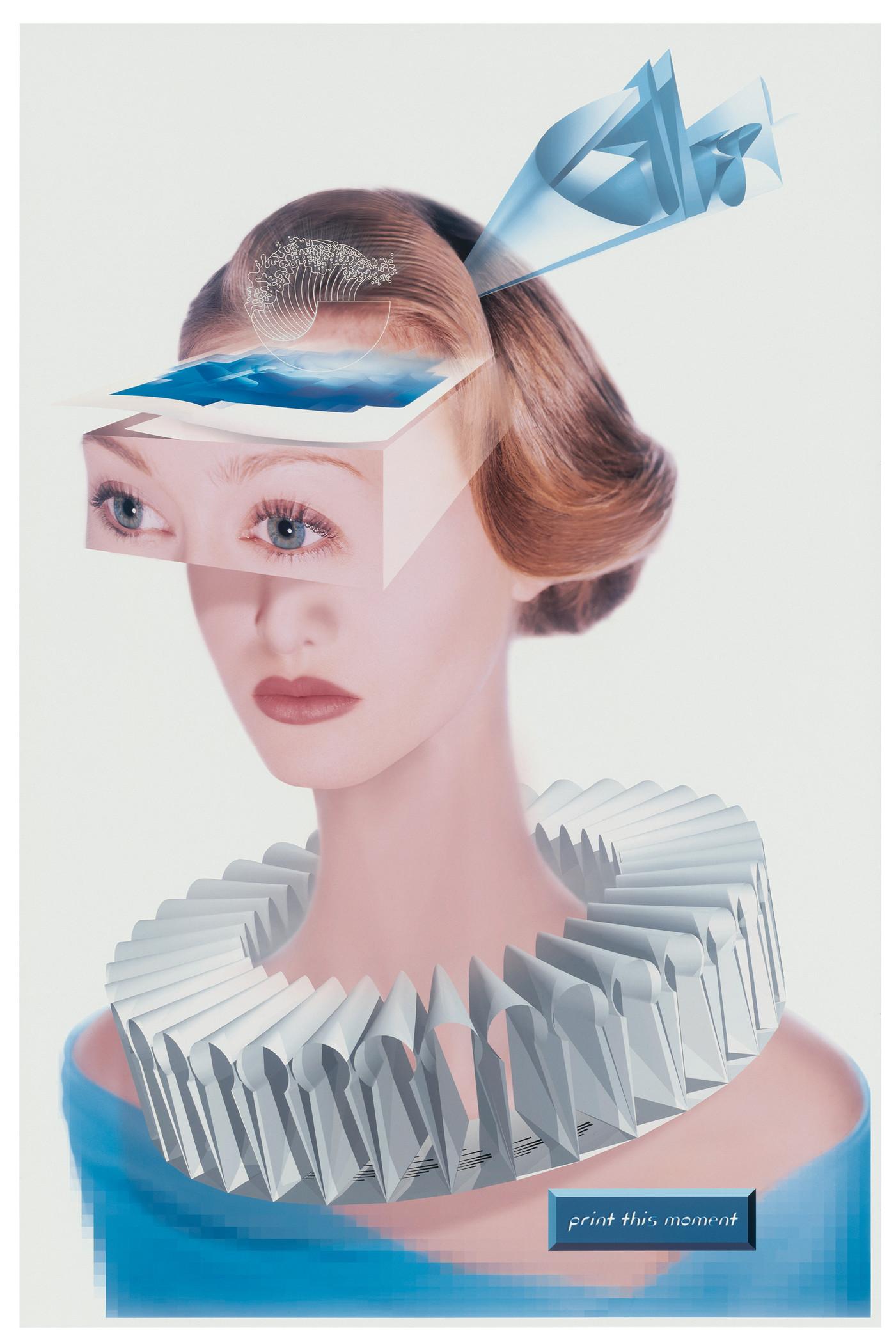

So, what light does the new initiative “PST ART: Art & Science Collide” shed on this age-old marriage between disciplines? It’s difficult to say, since the show’s scope is so wide-ranging it seems to encompass all art– past, present, and perhaps future. In essence, both disciplines are about problem solving, asking what if, and then finding a way to make it so.

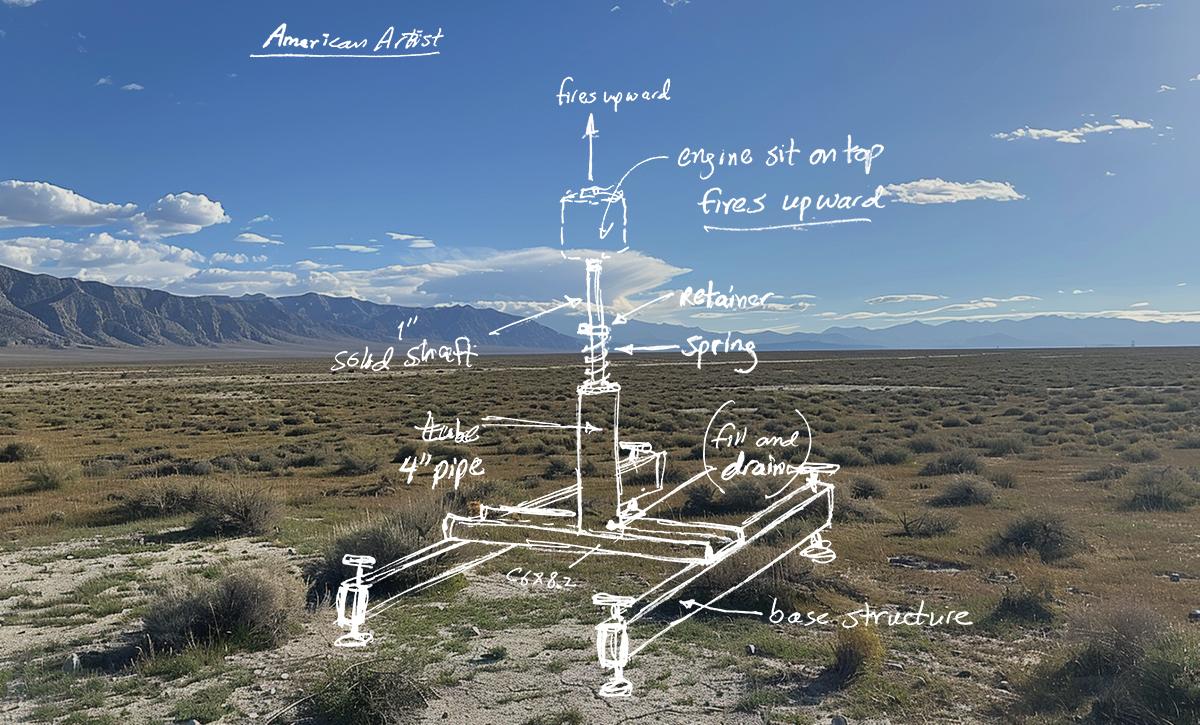

Funded by The Getty Center to the tune of $20.4 million, the periodic presentation presents 70 exhibits across 80 institutions throughout Southern California, with nine of them occurring on the museum’s home turf in Brentwood. This year’s PST began with a bang on September 15th, when Cai Guo Qiang presented “We Are” at the LA Coliseum before hundreds of spectators gathered on the field.